We all have stories when the interview did not go according to our expectations. Either our performance was insufficient, or the other side was mean or cruel. I want to share the story of one such interview so that it might be a reminder for me in future and, hopefully, for somebody else, an excellent lecture a one didn’t need to pay for.

This article is a short story from a technical interview with a German tech company I conducted in the early summer of 2022. I will not name the company, but it was an early seed-stage startup focused on a particular niche of the finance market with a well-defined product and roughly 50 employees around the globe. I interviewed for a full-stack developer position.

Screen call

As I do not know anybody inside the company, I can only say it looked fine from the outside. So I replied to the company’s headhunter on LinkedIn and arranged the first screen call.

The first screen call went good, and I liked the international environment. While total compensation was not significant, I liked the product and the idea of having an impact, the chance to making a difference. The startup had a working product for the first big clients in its niche and looked for ways to expand further. Consequently, expansion means headcount growth.

The screening call ended with a simple code review assignment. The company’s headhunter told me it should not take more than 20 minutes to complete.

The code review took me an hour to complete eventually. Later, the tech lead was very satisfied. The tech lead suggested only one slight improvement, which would increase code granularity. But I could debate whether the code would be better or worse with that single-line improvement.

After the initial screening call, the headhunter changed his approach and set a very formal tone despite being quite informal till the end of the screening call.

By the end of the first round, I got mixed feelings about the actual vibe in the interviewed company. But I pushed my spider-sense tingling aside and focused on the technical interview.

Technical Interview

My interviewer was the tech lead from a promising startup.

Straight from the start, the interviewer was 20 minutes late. So after the first 10 minutes on the empty Teams call, I sent the company’s headhunter a mail. Luckily the interviewer came within the following next 10 minutes. The only explanation I got was that interviewer somehow “lost” the interview appointment in his Outlook. I said to myself OK, as this can happen to anybody. No red flags have been raised yet. So when we finally started, it was already 6:00 PM (no time difference between the interviewer and me). So I thought it would be better to continue the interview rather than reschedule it for a different day.

The interviewer introduced himself and the company. Then he gave space to me to introduce myself.

As he was making the call all the time from his phone, I barely understood him. Then he gave space to me to talk about myself while he tried to switch the phone and join the call on his laptop. He basically didn’t care about anything I told him as I spoke. And until he joined the call on the computer with the proper headset on his head, I also barely understood anything coming from his mobile potato.

This introduction dance took roughly 15 minutes, and we stepped toward the technical part.

Single technical interview question

The interviewer gave me the code below and asked me to figure out what the code does and implement it. The following code is the code I started with:

public abstract class Event {

public interface Listener {

}

public void registerListener() {

}

protected void triggerListeners() {

}

}Excuse me, as it was not apparent what the code represents. Although I am a senior software developer, I do not know everything. Therefore if you know what should be the implementation of the following code, you are definitely worthy of the title software engineering oracle.

I took a minute, but I could not understand the idea of the exercise. Words are words, and implementation can have any form without correctly stating the problem and its context.

Even more, as said before, the first round of the interview process was a take-home assignment about code refactoring. And again, here at the interview, I have straight at the beginning poorly formatted Java code (I have never seen a Java interface implemented inside the class). Was it intentional, or am I missing something? Immediately, a thought fired through my head: How bad is the code in this company when I always get lousy code at their interview?.

After another few minutes of thinking and trying to figure out the problem angle verbally, I gave the interviewer a straightforward question: “What problem do I want to solve?” He answered me in the most challenging way possible, “Look into the code. It is all there.”

I will say it very openly – at that moment, I knew immediately I would not like to work with this guy at all.

As said before, words are words, and two method names and one empty interface do not tell me anything more about the problem context than a blank sheet of paper. You see, I did not ask what a concrete code implementation should be. What I wondered was what problem I wanted to solve. And the answer to this question is absolutely not “Look at the code!”.

Eventually, he expressed his idea of designing and coding Observer pattern from the starting code.

Throughout the interview, I got several times into the position I was cornered, and the interviewer introduced me to some sort of new scenario which asked me to change implementation based on the revised requirements. He did not provide me with the list of all scenarios at the beginning, yet he expected me to give a solution to the changes on the fly. Of course, anybody who has designed mutual entity interaction knows it would be nice to know the requirements at the beginning and not change them continuously. But I take it that this might show off a real-world scenario of continuous development.

It is debatable how fine-grained a solution you can and should create from the start. However, the situation was often open to interpretation and what I was thinking and providing in code was not what the tech lead was expecting as the goal of his desire. So there was a big mismatch between us. And rather than him stepping down and going along with my thinking, he consistently insisted on his version of the truth.

At that moment, he might do this interview question a hundred times, while for me, it was implementing Observer pattern from scratch for the first time in my life.

You can’t expect everybody to go with you all the way. People think differently, and in such a vast open space for interpretation, you should also be a partner with the candidate rather than be their nemesis.

Wonderful idiot

The week before this interview, I was at a local meetup in one tech company where the talk was on the topic of how to get a higher salary in tech [1]. And at the meetup talk, the term “wonderful idiot” was coined. Wonderful idiot is the kind of software engineer who saves the day, the best developer in the team, the kind of 10X developer. But the problem is that nobody likes him/her and wants to be friends with him/her.

Yes, you need wonderful idiots to do a job and save the day. But 99.99999% time, you need ordinary people around you. I immediately felt from the interviewing tech lead that he was a wonderful idiot. He decided to pick one thing from the whole of computer science and expected the candidate to be experienced just like him.

Note: Even if you think you need a “wonderful idiot” to save your company, let’s say only once per year, you should really take time and think about why is your company dependent on a wonderful idiot.

Well, guess what? Being a good software engineer today is not about knowing one thing extremely well, but knowing many things averagely.

When you are testing candidates on one thing and forgetting about the rest of job-requirement you are making a huge mistake.

End code

So minutes passed, and we slowly started moving towards the specific implementation of the Observer pattern. Moreover, the interviewer wanted me not only to figure out the Observer pattern implementation but also to create in a concurrently robust way and “expect the unexpected”.

The tech lead was testing not only specific pattern knowledge (what is a stupid idea) but also concurrency, error-proneness and testability of written code (without providing context at the beginning).

Throughout the interview, he gave me leads on what I should consider and how to implement the Observer. I have written my notes into the code below:

// What went wrong and why? No info regarding the problem - it is up to the candidate to figure out basically everything

// No info regarding behaviour - empty interface placed incorrectly inside the Event class at the beginning

public interface Listener {

void fireEvent(Event event);

}

public abstract class Event {

// volatile (direct lookup into the Heap) is not required as access can be replaced by Collections.synchronizedList(list);

// Threads store a reference in their caches, not the value of the reference.

// Therefore, direct access to the list through volatile is not required.

private List<Listener> list = new ArrayList<>();

// Use-case 1

// Insufficient solution - I have placed synchronized only on one registerListener

// synchronized blocked - Two thread access the same list.

// How do you synchronize access against race-condition?

public void registerListener(Listener listener) {

this.list.add(listener);

}

// Use-case 2

// Insufficient solution - synchronized needs to be placed on both methods

// synchronized blocked - Two thread access the same list, but one is adding, and the second is reading.

// How do you synchronize access against race-condition?

protected void triggerListeners() {

for (Listener listener : list) {

// Use-case 3

// Catching errors (I did not place any try-catch block around fireEvent()):

// Clue #1 - What is missing?

// Clue #2 - Imagine that this method works all day.

// Clue #3 - Imagine a click event on a computer mouse made thousand times a day.

// Clue #3 - Imagine you are the developer of the most used library for firing events.

// I guess what the interviewer wanted to say is to EXPECT UNEXPECTED

// DB is down, and the listener fails. If the first subscriber is a null pointer,

// the rest of 99 out of 100 firing events will fail as you did not catch any exception

// Wrap the code in a try-catch block to catch the exception

try {

listener.fireEvent(this);

// Use-case 4

// Interview questions: Why is it good to catch Throwable <-> Errors are also Throwable

// and you can not gracefully recover from them. (Errors terminate program flow)

// Usage of Throwable <- look into the Spring; it is legitimate to use catching Throwable

} catch (RuntimeException || Exception || Throwable ex) {

logger.error(ex);

}

}

}

}While technologies I use daily might heavily use the Observer pattern in the underlying tech stack, I have never implemented nor thought about it before. So I took the Design Patterns, a.k.a Gang of Four book, after the interview and read the whole chapter dedicated to the Observer pattern.

Look, I get it. Me not knowing the Observer pattern looks very stupid. But from my perspective, the Observer pattern knowledge is always within reach of the palm of my hand. Literally! And honestly, the Gang of Four book version of Observer does not very like the code provided at the beginning. So not knowing the knowledge which is in the book is not a big deal for me.

The end of interview

Forty minutes after the start, the interviewer decided that it was enough and would like not to continue further in the interview. As he started to give me not-so-persuasive feedback about my performance, he decided that it was not worth continuing with me further as my performance did not persuade him to continue. We mutually thanked each other and finished the call. It was immediate that I would not get a job in the company.

A week later, I also got a formal email with a short negative hiring reply, which included the phrase, "... The committee decided not to continue with your application." I do not know how many members that "committee" had. But I am pretty sure it contained at least one wonderful idiot.

Post Mortem

After an hour-long interview, I spent another three hours thinking about what could be improved and where I made a mistake. For example, was I a bad communicator? Or did I simply not know something because I do not use it? Eventually, I decided to summarise my notes and write this article for posterity.

What we have learned?

Is there any moral lecture in this story?

I think I can sum up a few points in which this failure enriched me:

- As an interviewer, come to the meeting always on time. The interview is mutual, and the candidate is also picking the company. Not being on time never looks good, on whichever side of the interview you are.

- Be properly connected and have your video on. Again, it is a mutual expectation for the interviewer and candidate to be connected with a stable connection and not transmit sound and video with 60's data link.

- Do not ask things in books and expect the candidate to know the answer. Not only did you conduct the interview with the same topic a thousand times while the candidate might see the problem the first time, but you are really asking about the things stored in books. Please don't be rude or criticise a candidate for something he does not know. And what is in books is not really something you should know by memory. That is why we created books in the first place, not to carry all the knowledge in our heads constantly, isn't it?

- Do not announce the final verdict at the end of the interview. Leave it on later.

- Also, do not state the problem itself as something the candidate should figure out on his own. You are the interviewer and need to state the problem the candidate should solve. If you design an interview for a candidate to come up with the creating problem statement and also demand a solid solution, you are making it wrong and wasting your and the candidate's time.

- When you offer an open question, do not expect everybody to solve it in your way and desire. There are multiple ways how to solve open questions.

Real world proof

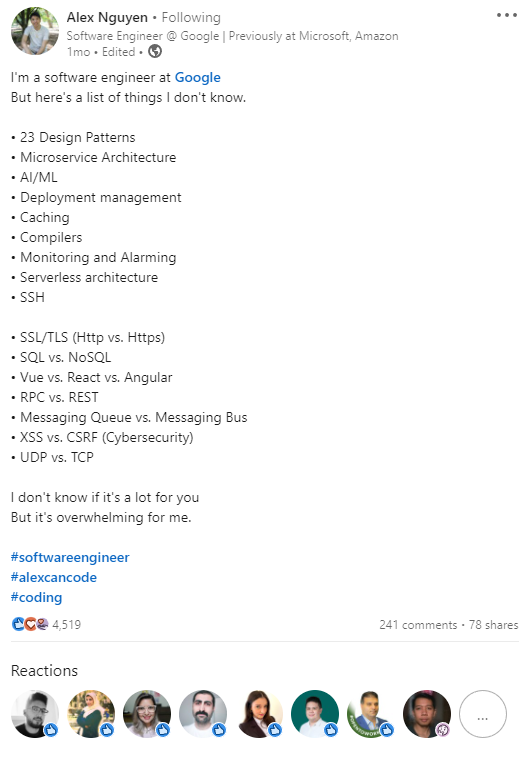

Several weeks after the interview, I have seen Alex Nguyen's LinkedIn post.

Original Alex Nguyen post on LinkedIn

When I was reading more at Alex's blog, I found that his current year total compensation is around 300 000 USD[2]. So this post only confirms my statement that the interview should not test things in the book and rather the ability of software developers to solve a problem effectively.

On the other hand, I have to take Alex's statement with a pinch of salt. If I paid somebody 300 000 USD a year, I would expect such a software developer to bring some value from Alex's list.

[1] https://www.meetup.com/pure-storage-talks/events/286587285/

[2] https://medium.com/the-weekly-readme/when-switching-companies-isnt-worth-300k-at-google-8d13e7876cda